Monday Magic: What a list of donkey sales can tell us about doing magic in Roman Egypt

A snippet of work I've been doing as I write Making Magical Matter.

Content warning: Magical handbooks from this period often mention violent acts committed against humans and animals. This week's post mentions violence against animals, both real and potential. Please be aware that this is hard work (I know, because I find it rough), so be cautious when you read. Because this is all about donkeys, who are still among the most widely used animals in the world and often suffer a great deal of abuse at the hands of humans, if you want to support their care, please donate to The Donkey Sanctuary, if you can.

Today I'm sharing a snippet of research I've done for the last ten years on magical objects and texts from Greco-Roman Egypt. We start with something a little odd: the sale of a donkey between a priest and a soldier.

Sometime in the Roman Imperial Period (1 BC to 400 AD), an ex-priest of Hermopolis sold a donkey to a soldier of the Legio III Augusta. The donkey was male, had some scars, and cost, according to a contract for sale, around 1300 drachmas in silver coinage of the Augusti. The contract was translated and published by Nikolas Litinas back in 1999, along with a list of donkey sale contracts already discovered, and references to the cost of donkeys in Greco-Roman culture in literature by Varro and Pliny.

OK. But what does this have to do with ancient (or Greco-Roman) magic?

Well, donkeys are frequently mentioned in magical handbooks from the period. Some procedures involve making inks or smearing objects with donkey's blood. Rita Lucarelli has studied the role of donkeys in these handbooks extensively, if you’re interested to know more. Two procedures I’ve worked with involve sacrificing a donkey to consecrate a figurine intended to protect a workshop and guarantee the business will prosper. I’m going to focus on one of these today, GEMF 57/PGM IV.2373-2440.

Let's take a look at those procedures before we start thinking about how donkey sales fit into all of this. Two procedures in the group of handbooks I study involve creating a figurine that, if it's inserted into the walls of a workshop, will ensure good business, prosperity, and success. The figurine the practitioner makes is of "the Wandering Isis", which makes reference to Isis, especially during the time after her brother-husband Osiris was dismembered by his brother Set, and she had to go hunting for all his body parts.

After making the figurine, the practitioner has to conduct a ritual to "activate" it.

Now, some experts will remind me that these procedures may not actually have been conducted, or that materials were swapped out for others that were less difficult to get hold of. Practitioners might, for example, make a fake donkey and sacrifice that instead. But, in the particular case of the sacrificed donkey, there is also a mention in the text that the meat should be roasted and eaten.

So maybe it's a real donkey? If it's a real donkey, what does that mean, and where did the donkey come from?

(Side note: the magical handbook we're talking about here has less physical evidence of being used than others, like GEMF 15/PGM XII, so it may not have been used. It's dated to the fourth century by the most recent research by the Transmission of Magical Knowledge project at Chicago. We always have to wonder how much these rituals were being performed at all, but for now, let's assume that this or something like it was being performed, given that literary sources like Apuleius's Metamorphoses contains references to figurines being used as protective devices in the stables when Lucius wakes up as an ass... but that's a whole other conversation.)

As somebody who studies the universe of animals, humans, and materials that went into magical procedures, I wanted to know where they came from. Sometime late in 2022, I fell down a rabbit (donkey?) hole, on a quest to find out where people got the materials involved in making something magical, and ended up with Litinas's list of donkey sales.

Here's the idea: we don't have much information on where ritual specialists who made objects got these materials. Sometimes, instructions will mention something specific, like "iron from a leg fetter", or a set of instructions for picking a plant. I'm currently writing up my book chapter on where magical practitioners got their materials from, and it's incredible to see that so many ingredients, furniture, incense, animals, and other bits and pieces are listed but their sources aren't.

Plants have rituals, listed both in the magical handbooks and in ancient literature, especially Theophrastus and Pliny the Elder. But other materials don't. It might be, therefore, that they were being bought, either traded or simply purchased at a market.

I've been thinking about how magical practice is embedded in the economies of the world, but rarely discussed in this way. Down the street from where I live, there used to be a shop that sold the modern equivalent of the objects practitioners made in Roman Egypt: figurines of relevant deities intended to bring prosperity, incenses and oils, stones and amulets, furniture and other items necessary for the modern magical person to use.

Practitioners in Roman Egypt were, according to work by Jacco Dieleman, survivors of the gradual decline of the great temple complexes of Ancient Egypt. As the Roman state took their land and other assets, priests and their families had to find other ways to survive. Hence, using what they already knew about effective ritual practice in their local communities, often for money.

This might appear an unseemly way to approach the study of ritual magic, but there was and is power in something being costly. It's one way that something can be difficult to get hold of, a vital characteristic of a lot of magical materials. Gold, silver, expensive oils and incenses, all carry that sense of being special because they're expensive.

Does this apply to donkeys as well?

The sale of the donkey by the ex-priest suggests a price of 1300 dr in silver. I have two questions from that: Is that typical? And is that expensive?

Nikolas Litinas has collected both literary mentions of donkey costs and actual contracts of sale. As I often find when I compare ancient literature and evidence of actual practice, the two are very different. Varro mentions costs ranging from 40,000 to over 400,000 sesterces. but actual donkey sale contracts show that, while in the early Imperial period, donkeys cost 80 to 200 drachmas, as time went on the costs went up to 3000 or 4000 drachmas.

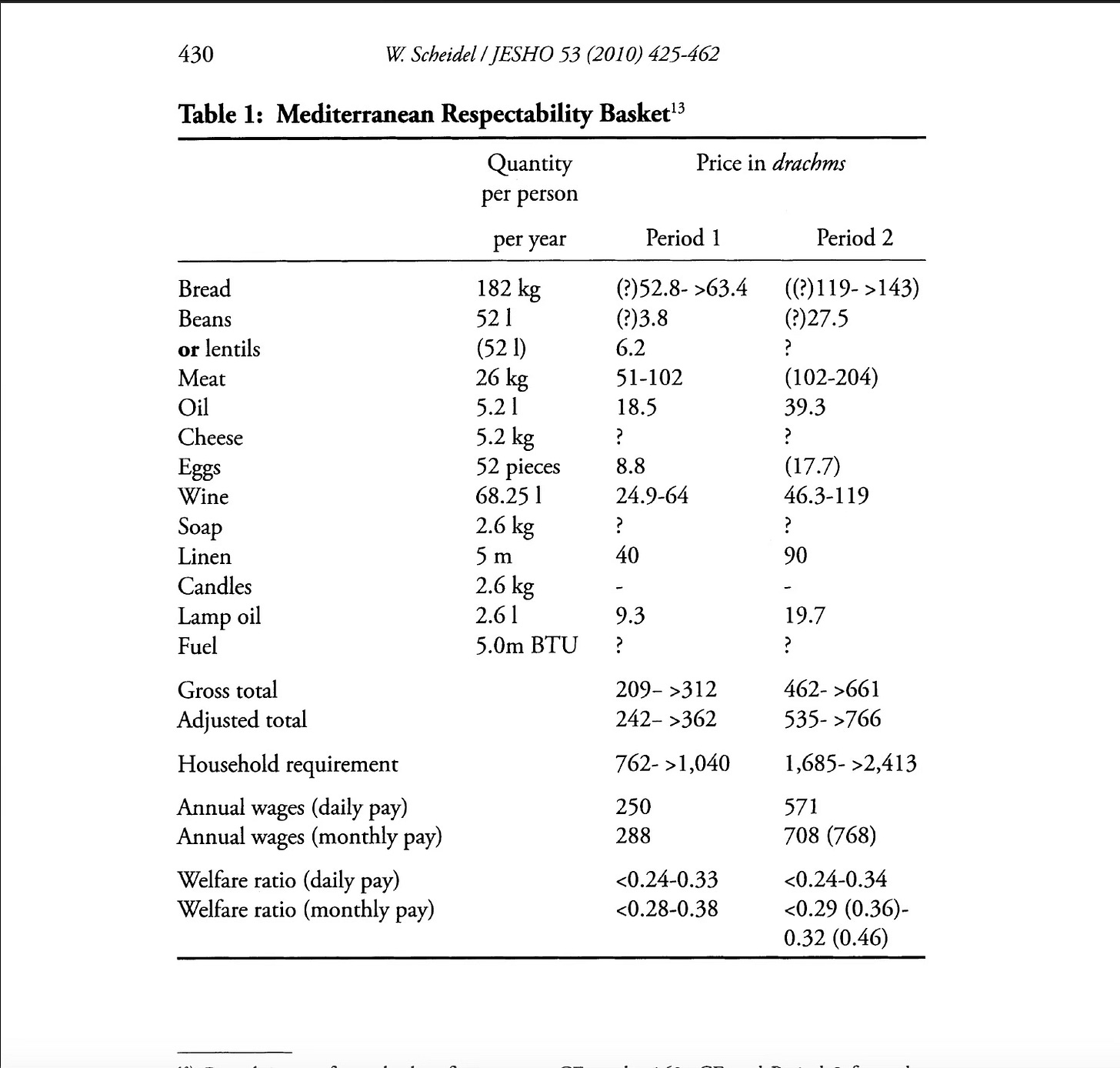

The next problem is figuring out whether that's a lot of money. For this, I went to Scheidel's work on the economics of Roman Egypt, hunting for information on incomes. This is difficult to find and assess, but in 2010, he did produce an estimate for labourer annual incomes starting at around 250 drachmas per year, going up to 780 per year in the later period (see the screenshot below).

Based on the contracts of sale, purchasing a donkey would have been out of the reach of a labourer, certainly by the later Imperial years. In the early years, it's more like somebody paying for a decent car. Donkeys are incredibly useful animals to have around. They can be used to help plough fields, pull carts, carry loads and people, and make more donkeys.

In Ancient and Roman Egyptian magic, they were associated with Seth (Set) or Typhon, one of the great antagonists of the Egyptian and Greco-Egyptian pantheon. Disorder, chaos, and disruption are a fundamental part of the magic found in the Greek and Egyptian Magical Formularies, even when practitioners were hoping to achieve something positive like blessing a workshop with good business.

On another level, because the procedure I'm interested in here is one that also draws on the myth of the Wandering Isis, perhaps sacrificing the animal associated with Set, who dismembered his brother Osiris in the first place, is meaningful. Cultural and mythological associations aside, offering up something so expensive associated with hard work would also lend the whole procedure extra magical power.

What can we say about all of this so far? Well, if you were going to attempt this ritual in full, you'd need to be able to afford the cost of the donkey, all the other materials like incense and oils and furniture—it's not the kind of procedure performed by somebody who isn't already well off, or who doesn't have access to expensive, imported materials. It may also provide further evidence that procedures weren't performed in their entirety in reality because the cost was prohibitive.

This kind of research is still in its early stages and as much as it would be great to do an "economics of magic" approach, my focus has been broader and based more in the theoretical underpinnings. This is something for a future fellowship, maybe, or a book. However, I hope this serves as an example of the kind of work that might be possible to understand how magic and ritual practices fit into the broader economy of Roman and Late Antique Egypt.

Some references:

The procedure in question is GEMF 57/PGM IV.2373-2440. The translation work in Chicago is ongoing, so I've been working with my own translations and the prior version published by Hans Dieter Betz in 1986.

Scheidel's work can be found here, but requires JStor access: http://www.jstor.org.manchester.idm.oclc.org/stable/20789801

Litinas's work can be found here: https://www.philology.uoc.gr/uploads/nikos_litinas_sales_of_donkeys.pdf

*Unskilled is a contentious term. It's used in economics a great deal but there is a whole discourse concerning whether any work can be truly considered "unskilled". Another conversation for a later time.

This is really interesting, especially the thread about former priests finding new ways to make a living and setting up the ancient version of Mystic Eye Botanica. Sounds like a story idea there!